By Kevin Zimmerman, Video Game Writer and Narrative Designer

In the world of open-world games, not all worlds are created equal. In fact, for narrative designers, open-world games present a slew of storytelling challenges. On one hand, there’s crafting a detailed, overarching narrative while still allowing for player freedom. And on the other hand, there’s creating an open world where telling a coherent story seems impossible. Today, let’s focus on the latter: open-world games with minimal to no overarching plot. In my opinion, this is the more difficult sub-genre of open-world games to write for. Next week, we’ll explore open-world games such as “The Witcher 3” or “Horizon: Zero Dawn” which lie at the other end of the open-world spectrum, retaining a strong overarching narrative.

The Narrative-Light Open World

At first glance, the idea of an open-world game without a strong overarching narrative might seem counterintuitive. After all, aren’t stories what pull us into the game, giving our actions purpose and direction? Well, games like “Elden Ring” and “Zelda: Breath of the Wild,” demonstrate that other storytelling aspects such as worldbuilding, lore, and an engrossing atmosphere can compensate for a less prominent plot. In fact, this style of narrative design shares much with Metroidvanias, where the focus is on the freedom to explore rather than following a strict storyline. For our narrative purposes, let’s bundle these two genres together and call them “Open Metrodvanias”… because we can!

Why Narrative-Light?

Before going any further, let’s address the elephant in the room: what’s so hard about just adding a good story to these kinds of open-world games? Well, the challenge with true open-world games is the issue of non-linearity, or more specifically, non-causality. Traditional stories have a beginning, middle, and end in which each event causes the next event to occur. But in a world where players dictate their own path, this structure crumbles almost immediately.

Before you get angry, it’s true that some stories, like “Pulp Fiction” or “Cloud Atlas,” play with non-linear storytelling, but these stories require careful orchestration by a director/writer to ensure that each scene, even if chronologically out of order, contributes to the overall narrative impact. In other words, pacing is still very much present even if the plot is non-chronological. In a truly Open World, however, the director and writer take a back seat. We tell the player they can play, go, and do whatever they want! Therefore, the solution for some games is to simply discard the overarching story altogether and embrace a more ambient narrative experience–the freedom to explore a world made of interconnected stories and experiences rather than a single, linear journey.

A World Made of Puzzle Pieces

Consider indie titles such as “Hyper Light Drifter,” “Her Story,” “Gone Home,” or “The Witness.” Each of these games excels at creating narrative through exploration and discovery–each in its own way. Instead of experiencing a story “on rails,” players gather clues or artifacts, piecing together the story in a sequence that may vary drastically from one playthrough to the next. To do this, the game’s minimal story usually leans on archetypal, mythological, or familiar tropes that can be told in just a few sentences. At the end of the game, when you finally piece that simple story together, the reward is a sense of wisdom or clarity. Think of it like putting a jigsaw puzzle together to see what it looks like as a whole, rather than traveling from A to B to C. The atmosphere and the world take precedence over a predefined plot.

Environmental Storytelling: Painting Stories Without Words

So how are we supposed to insert storytelling effectively into narrative-light open worlds? Well, let’s first talk about Environmental Storytelling. Perhaps the primary tool when writing for our Open Metroidvanias, the environment goes way beyond mere scenery and becomes a storyteller itself. Environmental storytelling allows for the crafting of rich narratives without direct dialogue. Ruins of civilizations, the placement of everyday objects, or transitions between biomes serve as clues for players to discover the world’s history and secrets at their own pace.

“Hollow Knight” is a great example of this approach, with its setting in the fallen kingdom of Hallownest. Here, the environment invites players to uncover its story through exploration, from dilapidated structures to cryptic inscriptions that hint at ancient tragedies. Detail, detail, detail. That’s the key to getting environmental storytelling right. Subtle cues, such as a forgotten nail or the statue of a hero, hint at tales of victory and loss, pushing players to engage more deeply with the game and even build “head canon” of their own.

Lore and Backstory: The Foundation of Your World

Similar to environmental storytelling, bulking up on lore and backstory can deliver incredible narrative impact, even in games that are otherwise narratively light. Lore and backstory offer players a rich diversion of history, culture, and intrigue to explore at their leisure–even outside the game itself on official Twitter accounts or Wikis. Even more, an Open Metroidvania’s lore and backstory can play a crucial role when it comes to things like environmental design, side quests, enemy design, and even music. So, narrative designers should thoroughly explore lore and backstory in an Open World game before doing anything else.

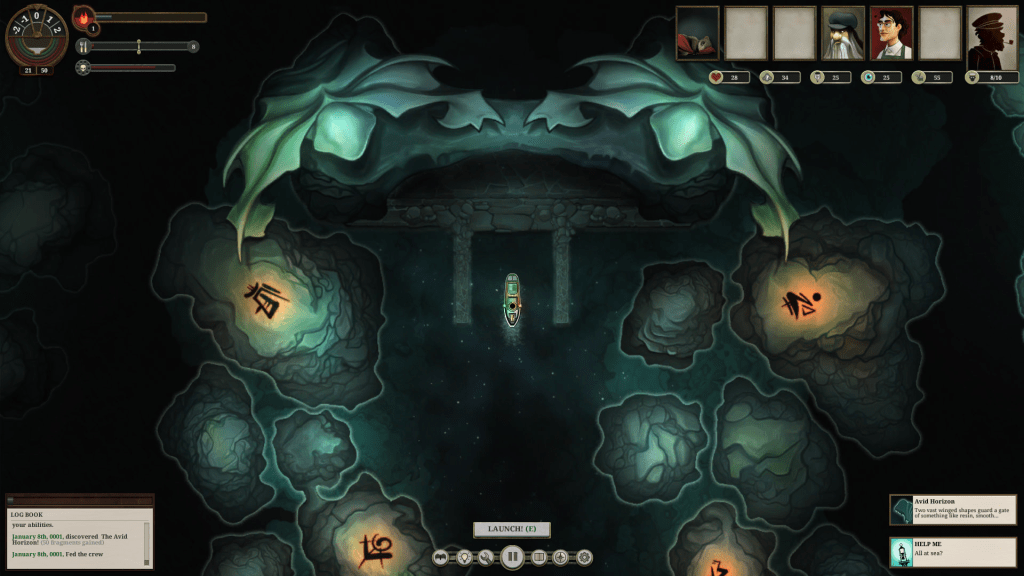

“Sunless Sea” is a prime example of this principle in action. Set in the dark and mysterious waters of the Unterzee, it doesn’t rely on a strong, overarching narrative to propel the player forward. Instead, it weaves a compelling world through the scattered lore and backstories of its characters, islands, and the sea itself. The world’s secrets and stories get uncovered piece by piece, through exploration and interaction, reconstituting the lore that makes the game’s universe feel vast yet intimately detailed.

The Art of the Side Quest

But isn’t it possible to tell some kind of traditional story in these Open Metroidvania games? Well, yes, kinda. That’s where side quests and bosses come in. Side quests are more than distractions in this genre, like they are in others—they’re opportunities to deepen the game’s world and engage players with its lore. Side quests can introduce stories that, while tangential to the main narrative, are crucial for a full appreciation of the game’s universe. They allow for exploration and discovery in ways that the main quest might not, providing the player a unique blend of freedom and storytelling in the game’s overall experience.

“Elden Ring” serves as a great example of this strategy at work, particularly with the subplot involving Malenia, Blade of Miquella. Despite the game’s sprawling, often vague main story, it’s through Malenia’s side quest that players encounter one of the most compelling narratives in the Lands Between.

Although being one of the most notorious genres when it comes to storytelling, let’s summarize what we’ve gone over today when it comes to raising the quality of your stories in the “Open Metroidvania” genres:

TL;DR Narrative Considerations for Narrative-Light Open Worlds

Atmosphere is Key: Craft a world where the atmosphere is rich, stylized, and immersive, encouraging players to explore and uncover its mysteries.

Non-Linear Storytelling: Adopt non-sequential storytelling methods, allowing players to piece together the narrative in a personalized and engaging whole.

Environmental Storytelling: Utilize the game’s environment as a silent narrator, where every ruin, item, and biome shift tells part of the world’s story, engaging players in a dialogue without words.

Lore and Backstory: Embed deep lore and backstory into the world, enriching the player’s exploration with history, culture, and intrigue that feels organic and compelling. Consider providing players with additional lore and backstory outside of the game as well.

Rich Side Quests/Bosses: Infuse your game with side quests, bosses and sub-plots that add layers of depth and color to the world, even if their impact on the overarching narrative is minimal.

World Building: Ensure that every game element, from the environment to NPC interactions, contributes to a cohesive sense of place and atmosphere, making the world feel alive and dynamic.

If you’re currently seeking a narrative designer or game writer who can bring your vision to life, let’s connect! Reach out to me here or on LinkedIn—I’m eager to dive into your project and explore how we can collaborate to create a game that not only captivates but also leaves a lasting impact on your players. Also, share your thoughts and questions in the comments below. Are there specific challenges you’ve faced in narrative design? Or perhaps you have a success story where narrative design profoundly impacted your game?

Thank you for joining me in this discussion, and I look forward to sharing more insights into the narrative design process. Keep an eye out for the next installment in this series, where we’ll cover Narrative-Rich Open World games!

Your next game-changing story starts here.

Leave a comment